One woman actually changed the universe, or at least how we see it. Cecilia Payne-Gaposchkin, born in England in 1900, was an astronomer and astrophysicist.

She began at the University of Cambridge in 1919 and a lecture about Einstein’s Theory of General Relativity inspired her to study astronomy. Believing that the United States offered more opportunities to women, in 1923 Cecilia moved from Cambridge, England, to Cambridge, Massachusetts, to study at the Harvard College Observatory.

When Cecilia began at Harvard, many scientists believed the composition of stars was similar to that of the Earth. The scientists saw seven different absorption patterns, which led them to believe there were seven different stars, with varying combinations of the same elements found in Earth’s crust.

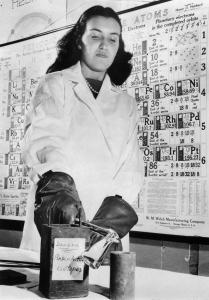

Photo courtesy of Harvard Square Library

Cecilia was not so quick as to agree with these conclusions. She proposed the seven patterns corresponded to different temperatures. With her background in quantum physics, Cecilia was able to apply her knowledge about ionization. Higher temperatures caused ionization, which meant ions of the same atoms with different absorption patterns. She knew the extremely hot temperature of the Sun would cause the atoms to ionize, and that these excited states would show up as different absorption lines on the spectra. Using the equations created by Indian astrophysicist Meghnad Saha, Cecilia discovered the sun was made of mostly hydrogen and helium.

Astronomer Henry Norris Russell was wary of this conclusion and persuaded Cecilia to not include it in her thesis. In her 1925 Ph.D. thesis, “Stellar Atmospheres”, Cecilia determined stars are mostly composed of hydrogen and helium but added a note that she was probably wrong.

Photo courtesy of FeedBox

Despite the controversy, Russian astronomer Otto Struve called her thesis “undoubtedly the most brilliant Ph.D. thesis ever written in astronomy.” Cecilia received her Ph.D. in astronomy from Radcliff College (now Harvard College Observatory) because Harvard University did not grant doctoral degrees to women at the time. Harvard also did not recognize female professors, so for many years, Cecilia settled with being a technical assistant. In 1956, Cecelia finally became the first female professor and the first female department chair at Harvard.

Four years after Cecilia’s thesis was published, the dissenter Russell admitted Cecilia was correct in her theory, and even published how own paper on it. However, this recognition was too late.

Cecilia never received enough credit for her ground-breaking work in astronomy, but her feats did not go completely unnoticed. Ironically enough, Cecilia was awarded the Henry Norris Russell Lectureship of the American Astronomical Society in 1976, 20 years after Russell’s death. Cecilia also has an asteroid and telescope named after her.

Cecilia’s work ushered in a new era in astrophysics, and we have her to thank for much of what we currently know about stars. Being a young woman, many older scientists were threatened by Cecilia, but she did not let that stop her. In her speech accepting the Henry Norris Russel Prize, Cecilia explains, “The reward of the young scientist is the emotional thrill of being the first person in the history of the world to see something or to understand something. Nothing can compare with that experience… The reward of the old scientist is the sense of having seen a vague sketch grow into a masterly landscape.”

More about Cecilia:

https://www.britannica.com/biography/Cecilia-Payne-Gaposchkin

https://www.aps.org/publications/apsnews/201501/physicshistory.cfm

https://www.youtube.com/watch?time_continue=330&v=I_qF-jTY2zY

https://www.aps.org/publications/apsnews/201501/physicshistory.cfm

Women in Science: 50 Fearless Pioneers Who Have Changed the World, Rachel Ignotofsky